The Philippines vs. China: The Real Fight in the South China Sea

by Richard Javad Heydarian, Huffington Post.

Heydarian is regular contributor to major international publications and think tanks on Asian geopolitical and economic affairs; author of “Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China, and the Struggle for the Western Pacific."

Though China has effectively boycotted the arbitration proceedings at The Hague, the Arbitral Tribunal has (once again) given Beijing the opportunity to respond to Manila's claims and arguments. From the Philippines' voluminous memorial, submitted in March 2014, to the Philippines' additional arguments, submitted a year after, China has been repeatedly given the opportunity to make a counter-claim and defend its case. No wonder then, the arbitration procedures has taken such a long time.

Assuming the Philippines wins the jurisdiction argument on at least some of its claims, we are looking at an extended period before there will be a definitive verdict at The Hague. So far, China has at best only produced a position paper (Dec. 7, 2014), which directly questions the appropriateness of compulsory arbitration as well as the competence of adjudication bodies under the aegis of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to oversee the South China Sea disputes.

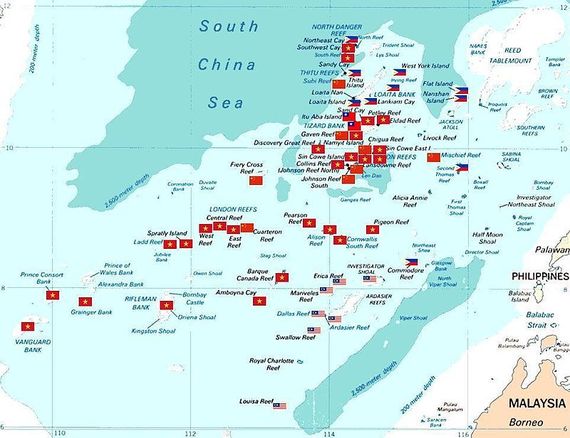

While the Philippines is waging the snail's pace legal warfare, China is dramatically altering facts on the ground on a daily basis. By all means, the real struggle in the South China Sea is to protect your position on the ground, defending every inch of your territorial claim lest others will Darwin you out. For long, the Philippines foolishly neglected fortifying its position across the Spratly chain of islands and its 200 nautical miles Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). It is high time for the Philippines to learn from other claimant countries and optimally defend contested features under its control.

There are signs that the Aquino administration is indeed shifting its attention to the frontline. Thankfully, the Philippines has at last started to repair its dilapidated, rusty fortification in the Second Thomas Shoal. The question is: Why only now? Since the early-1990s, when China coercively wrested control of the Philippine-claimed Mischief Reef, the Philippines has been acutely aware of China's territorial ambitions in the South China Sea.

A Tribunal under Siege

An additional complicating factor in the Philippine-China arbitration showdown is that the Arbitral Tribunal itself is facing an acute dilemma. Though Art. 9 of UNCLOS doesn't prevent the resumption of the arbitration procedures in absence of one party, the Tribunal is nevertheless extremely concerned with the legitimacy of the whole procedure -- and it has obviously been slighted by China's explicit snobbery.

Collectively, the judges at the Tribunal have consistently expressed their openness to Chinese engagement of the arbitration process, stating how the arbitration body "remains open to China to participate in the proceedings at any time." So we are talking about a quite open-ended legal struggle. The Tribunal also turned down thePhilippines' request for expediting the case by simultaneous adjudicating both the jurisdiction issue as well as the merits of the Philippines' case.

The United States, which possesses the world's most powerful navy, has yet to ratify the UNCLOS, mainly because of the intransigence of hardline elements at the U.S. Senate. (Note: The U.S. Navy, however, observes UNCLOS-related provisions as a matter of customary international law.) The last thing the Tribunal wants is to test China's -- the second most powerful country on earth -- implicit threat to withdraw from UNCLOS altogether.

For the Tribunal, as much as it would want to defend the Philippines' claims, it also has an interest in making sure it doesn't fully estrange the great powers, which actually undergird the global order.

One of the most fundamental limitations of the Tribunal is that it can't exercise jurisdiction on the question of ownership and sovereignty claims in the South China Sea. At best, it can question the validity of China's sweeping Nine-Dashed-Line claims as well as the admissibility of its artificially-created islands.

Limits of Law

Both China and the Philippines have expressed reservations with subjecting their territorial claims to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which is the body that can actually adjudicate on sovereignty claims. In short, international law as a mechanism to directly resolve sovereignty-related disputes is out of question.

Although, it seems many Filipinos have misunderstood -- partly because of the overly upbeat pronouncements of the Philippine government and the shortcoming of the media -- the ongoing arbitration at The Hague as one that involves direct adjudication of territorial claims. It may take up to three months before the Tribunal announces its decision on whether it can exercise jurisdiction over the Philippines' case against China.

During the recently-concluded oral arguments on the question of jurisdiction, the main challenge for our lawyers was to prove that (a) the Philippines' memorial transcends the question of sovereignty claims and that (b) compulsory arbitration is the only way forward, since both parties have supposedly exhausted all alternative options. So both issues of jurisdiction and admissibility had to be addressed simultaneously.

Assuming the Philippines wins the jurisdiction question, at least on some of its arguments, then we are looking at another lengthy round of hearings and clarifications before a final verdict can be announced. The Tribunal will most likely again provide China another opportunity to respond to the Philippines' at each succeeding rounds of hearings.

If the Tribunal categorically turns down jurisdiction on all of the Philippines' main arguments, then as a leading Filipino maritime law expert Jay Batongbacal puts it:"Manila might find its legal case abruptly ended and need to completely rethink its entire approach to the SCS disputes..."

Another option is the establishment of a "conciliation commission" (under Annex V of UNCLOS) under the aegis of the United Nations. The problem, however, is that the commission's final adjudication will not be binding, assuming China will agree to participate at all. So at best, we can get an advisory opinion on the South China Sea disputes. - Read full story on Huffington Post